UAH engineering alumna, Tia Ferguson, in Antarctica, 2008.

In 2008, Tia Ferguson, (MS, electrical engineering, ’03) ventured to a place so remote and forbidding, even veteran world travelers can be daunted by the prospect of such a journey. That was the year she trekked to the bottom of the world to help retrieve a NASA experimental package. Ferguson was part of the team that traveled to the landing site to pick it up.

An alumna of The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH), a part of The University of Alabama System, Ferguson spent four weeks in Antarctica assisting with the recovery of a science experiment dropped from a balloon near the South Pole. Her job as an engineer at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) gave her the opportunity to travel to the world’s most desolate terrain, a trip she had never imagined might be part of her job description in those days.

Around this time, the alumna had been doing mechanical design for balloon, telescope, satellite, rocket and ground experiments.

“I’ve always been involved with scientists throughout my career,” Ferguson notes. “I was in project management, and I wanted to go back into tech. Basically I did everything, the concept, the design, contracting the machine shop, the integration and testing, and even operating. Getting the gondola to launch, from cradle to grave.”

Ferguson flew from Christchurch, New Zealand, to Ross Island, Antarctica, on a C-17 military aircraft.

NASA asked Ferguson to help with the Antarctic recovery because she had had prior experience recovering a balloon science experiment, NASA's Deep Space Test Bed, in New Mexico, a package she had designed in 2005.

“One of our payloads in New Mexico was a student initiative to build science experiments on our test flight, and UAH won one of those,” she says. “So I worked with UAH to develop an experiment that flew on the gondola. It was one of their senior design projects that year.”

The majority of Ferguson's four weeks in Antarctica, from Jan. 4 to Feb. 5, 2008, was spent at McMurdo Station. McMurdo is a science research facility operated by the National Science Foundation. The station is located on Ross Island just off Antarctica's eastern coast. The faraway base held a number of surprises for the UAH graduate.

“It was more industrial than I expected,” Ferguson says. “The smell of diesel, no earthly smells, only machine smells. It was also warmer. The temperature hovered around the 30s and 40s Fahrenheit, while the temperature at the pole was much colder, close to -40F with a wind chill factor of -80F.”

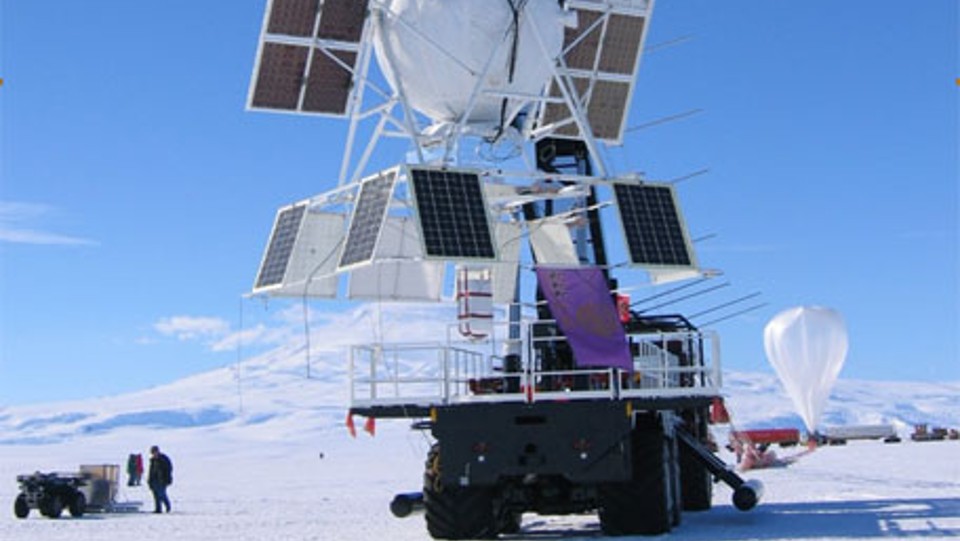

Though she played no role in the design of the Antarctic package, the alumna was understandably excited to be a part of the recovery team. The balloon circled above the continent for about two weeks until the experiment was released to fall back to Earth on a parachute. The experiment was called ATIC, which stands for Advanced Thin Ionization Calorimeter. Attached to a large plastic balloon that floated high above Earth's southernmost continent, ATIC studied cosmic rays, particles traveling at nearly the speed of light.

The living quarters at McMurdo Station are in large buildings similar to college dorms. Ground transportation is mainly on buses equipped with large tractor tires for driving in snow and ice.

Though bleak and unforgiving, Antarctica is a prime environment to fly high-altitude balloons because of a unique circular wind pattern that develops during the Antarctic summer which causes balloons to circle the continent for several weeks. The balloons ascend to as high as 130,000 feet, approximately 23 miles, allowing the experiments to make observations about space matter in Earth's atmosphere.

ATIC's scientists had no way of knowing where the experiment would land when it was released from the balloon. As a consequence, the recovery team had to prepare for surviving in both snowy and high-altitude conditions in case the package landed on the high plateau in the middle of the continent. Team members prepared for this possibility by attending snow school and high-altitude training.

Once her training was complete, Ferguson was able to temporarily relocate to the South Pole to be closer to where ATIC had landed. The team flew in a small airplane to the landing site and took apart the experiment for its return to McMurdo.

The Advanced Thin Ionization Calorimeter, or ATIC, experiment was launched on Dec. 28, 2007. The experiment studied cosmic rays, a sample of matter from distant regions of Earth's galaxy.

“They know where it [the experiment] is,” Ferguson explains. “But the only controlling factor is when they cut it loose to land. Ours was one of the very few experiments that circled inward and landed near the central area around the South Pole. So that was really cool. I didn’t expect to get to go to the South Pole, but I was able to!”

The altitude of the inner plateau Antarctica can be quite a challenge for newcomers. “We took medicine for the altitude, and they gave us a week to acclimate before jumping into lifting and hauling,” the alumna remembers. “The frozen water around your eyelashes was a real problem. At the end of the day you had all this ice caked on like icicles and it made it hard to even blink.”

Other physical demands were noteworthy as well. “It took two days to get the experiment recovered,” Ferguson says. “It weighed about 3,000 pounds! I never got cold, because we were hauling it back to the plane. But also we were trying not to sweat, because that is when you really get cold."

A native of Natchez, MS, Ferguson started working for NASA straight out of college. After coming to Marshall, turning to UAH proved to be a natural choice for obtaining an MS in electrical engineering.

“So I came to UAH for an electrical MS, with a major in optics,” she says. “I took a lot of classes after hours after work, eventually able to get a fulltime study in 1998-99, which was good, because that’s when my son was born. I loved mechanical engineering, but I like the testing aspect of electrical. UAH was very convenient, but also has a great engineering program, and my classes on micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS) were very fascinating. Back then this was before you had MEMS accelerometers in your car, micro sensors and things like that. So this field has really exploded since then.”

These days Ferguson is the Director of the Space Systems Department, the kind of role she has seemingly been destined to fill since her earliest days at MSFC.

At snow school, visitors to Antarctica learn to build snow walls.

“We have about 600 government and contractor engineers who are focused really on all aspects of what NASA is doing involving space,” she says. “Our engineers wrote the software for SLS [Space Launch System] in house, life support systems for ISS [International Space Station] and we are doing insight for human landing software and avionics. We just launched a telescope that studies high energy x-ray polarization of black holes and other interests in the galaxy. The telescope is commonly known as IXPE for Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer. We are launching a solar sail on the SLS rocket that will travel to an asteroid, known as NEAScout. I’m in an executive position now, so I get to manage a lot of really smart people doing interesting things.”

Looking back on her exploits at the bottom of the world, one thing Ferguson will never forget is the day she left the southernmost continent behind. “I can still remember how distinct it was coming back to New Zealand, the smell of the vegetation. In McMurdo they have a greenhouse, so I used to go hang out in there a lot because they had plants. That was what I really missed. But I will never forget the flight from McMurdo to the south pole, six hours of untouched beauty, the most beautiful experience to see these pristine mountains covered in snow and the ice fields.”

And what does she anticipate for her future now?

“To me, it’s so exciting that we are going to the Moon and Mars,” she says. “Being a part of taking people where we haven’t been before. The whole future of exploration is fun and fascinating to me!”