Researchers turn to “citizen scientists” for help identifying gravitational waves

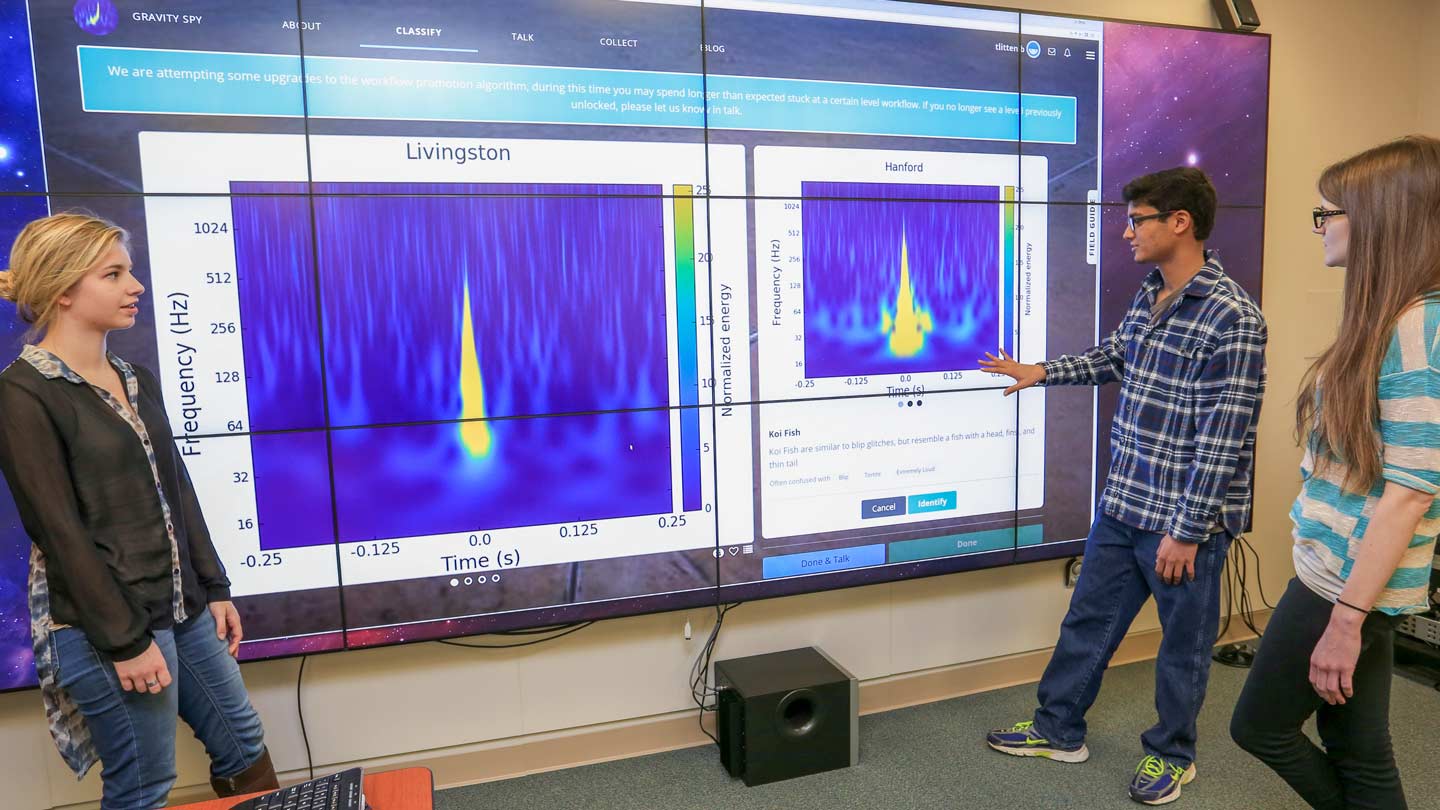

Space science graduate students Jordan Taylor, Jessica Page, and Ankur Shah are part of a team of scientists helping to classify gravitational wave signals detected by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory.

The term "crowdsourcing" has only been in existence for the last decade, but instances of crowdsourcing – in which stakeholders enlist the general public to provide needed services – date back hundreds of years.

One of the earliest known examples is the Longitude Act, which was established by the British Parliament in 1714. In hopes of reducing the frequency of maritime disasters, the Act offered a significant financial reward to anyone who could develop a simple, practical way to accurately determine a ship’s longitude at sea. The largest sum ultimately went to John Harrison, a self-educated carpenter and clockmaker whose marine chronometer would go on to revolutionize navigation.

Needless to say, crowdsourcing has become exponentially easier since the advent of the internet. With the click of a button, computer users around the world – known as "citizen scientists" – can help hydrologists analyze forest snow interception patterns, historians transcribe first-hand accounts from members of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps circa World War I, and chiropterologists identify the nocturnal behavior patterns of lesser long-nosed bats.

Now Dr. Tyson Littenberg, a research astrophysicist at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center and an adjunct professor in the Department of Space Science at The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH), is hoping they can help him as well.

The human brain is still the best computer in the world.

For almost a decade, Dr. Littenberg has been searching for the gravitational wave signals of black holes on behalf of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO). And late last year, when those signals were discovered, he was an integral member of a team that developed the sophisticated computer algorithms needed to comb through the data. Their findings were later published in over a dozen articles in six different journals, including Physical Review and The Astrophysical Journal.

While the discovery confirmed the last great prediction of Einstein’s general theory of relativity from over 100 years prior, however, it also introduced a new challenge: due to the extreme sensitivity of the LIGO’s two main observatories – one in Hanford, Wash., and the other in Livingston, La. – the data they gather are susceptible to disturbances from instrumental and environmental sources. "It’s called non-Gaussian noise, but we refer to them as glitches," says Dr. Littenberg, who was instrumental in facilitating Huntsville’s membership in the LIGO Scientific Collaboration. "We don’t really know what’s causing them, so it’s like solving a mystery."

Unfortunately, those glitches typically occur about once every second, vastly eclipsing the frequency of gravitational waves; thus far, says Dr. Littenberg, "there have only been two gravitational wave detections in all of human existence." The glitches’ time-frequency maps, or spectrograms, can also mimic those of gravitational waves, making it even more difficult to distinguish between the two with computers. So it falls to human beings, who are better able to recognize the subtle differences between glitches and gravitational waves, to teach computers how to do so – which is exactly where crowdsourcing comes in. "The human brain is still the best computer in the world," he says.

With this in mind, Dr. Littenberg and his LIGO colleagues at Northwestern University began laying the groundwork to harness the public’s brainpower back in early 2015. First they reached out to the crowdsourcing site Zooniverse, which hosts nearly 50 "people-powered" research projects. With Zooniverse on board, they then recruited researchers at Syracuse University and the California State University, Fullerton, to join their "glitch-solving" team. "We got the right people together with the right expertise," he says.

Dr. Littenberg hopes that Gravity Spy’s "citizen scientists" can help teach computers how to recognize the subtle differences between glitches and gravitational waves.

Now the results of those efforts have come to fruition: coinciding with the start of LIGO’s second observing campaign in late 2016, the crowdsourcing platform "Gravity Spy" moved out of beta and was officially launched. Funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation, Gravity Spy tasks volunteer citizen scientists with sifting through LIGO data and identifying "families" of glitches that can be sorted by machine-learning algorithms.

"We have two-dozen or so families of glitches, but the most important family so far is called the blip-glitch," says Dr. Littenberg, explaining that unlike gravitational waves, which always show up at the same time on both detectors, blip-glitches show up randomly. "They are the most-wanted glitches – and the bane of everyone’s existence – because they are frequent, we don’t know what causes them, and they look like the gravitational waves that we are trying to detect. So now Gravity Spy is going to solve them for us!"

If it does, the reward won’t be monetary as it was for John Harrison, inventor of the maritime chronometer. Rather it will be the satisfaction that comes from working together to advance humankind’s understanding of the universe. "Right now we know what the gravitational waves from black hole mergers look like," says Dr. Littenberg. "But once we can get a good handle on the glitches, we will have a better chance of finding new sources of gravitational waves – from supernovas and cosmic string to things we’ve never imagined."

And that, he says, "is when the really exciting science starts!"

Learn More

Contact

UAH Department of Space Science

256.961.7403

spa@uah.edu