UAH graduate student founds non-profit outreach organization to share love of history

Kelly Fisk Hamlin founded Wolf Gap Education Outreach to make history education accessible and affordable to public and home-schooled students in the Tennessee Valley.

This past fall, Kelly Fisk Hamlin became the executive director and principal educator of Wolf Gap Education Outreach, which makes history education accessible and affordable to public and home-schooled students in the Tennessee Valley. It's a role that's she is both passionate about and prepared for, after having spent the last few years pursuing her master's degree in public history at The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH).

"We realized schools in Giles and Lincoln Counties weren't going on field trips because they couldn't afford to rent a bus and travel to Nashville or Huntsville, so I thought what if I could bring those field trips to them?" says Hamlin, who is also the founder of the non-profit organization. "So far it's gotten a really good response, and we're trying to coordinate with the teachers' state curriculum requirements to design programs on subjects they've requested."

Hamlin initially earned her undergraduate degree in history and education from Sewanee: The University of the South. "I was going to go into international relations but then I had a really good history professor my first semester," says the Madison, Ala., native. "I realized I had been missing out on something that relates to every part of our lives. To me it's the most applicable subject of all and I felt crazy for ever thinking history was boring."

To me it’s the most applicable subject of all and I felt crazy for ever thinking history was boring.

When that didn't immediately lead to the museum job she was hoping for after graduation, however, she ended up working temporarily as a baker at her cousin's café. "That was a blast and I would have done that job for as long as I could," says Hamlin. But when the café closed, she knew she needed to "get back to what I'm passionate about." She also knew she wanted to stay in the area, having just met her now-husband and current UAH student Tyler Hamlin, a double major in psychology and philosophy. So she applied and was accepted to the Department of History's graduate program.

Soon after enrolling, Hamlin learned about the Department's brand new public history concentration. "I met with Dr. John Kvach, the director of UAH's public history program, and asked him if we could make something work for a master's degree," she says. "He agreed and so I ended up becoming the first graduate student in that concentration." Of course as soon as she decided she needed a master's degree to land a job at a museum, "I got a job at a museum," she laughs.

For the next five years, Hamlin divided her time between being a student and working at Burritt on the Mountain. There, as a historic park manager and educator, she was responsible for designing hands-on educational history programs for visitors to the 167-acre 19th century living history park. "It was neat to be able to take people back in time," she says. "I got to spend lots of time wearing an 1800s dress, churning butter and spinning wool!"

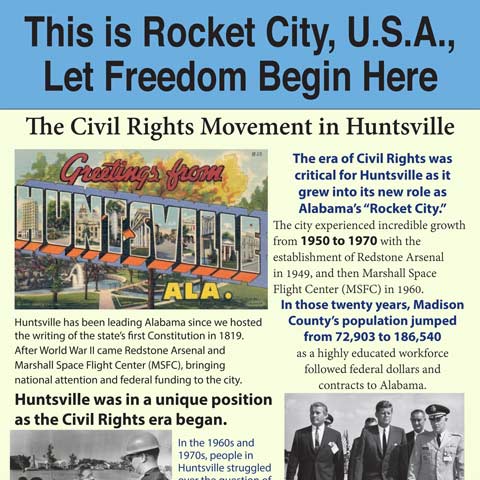

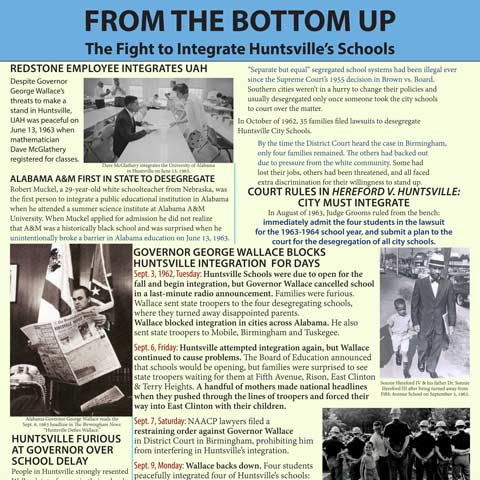

Her work there also dovetailed neatly with the research she was doing for her master's thesis. "Because it had to have a public programming component, I asked the curator if it could be added to the schedule of rotating exhibits," she says. Her idea met with approval, and in early 2014, Hamlin showcased her thesis exhibit "This is Rocket City U.S.A., Let Freedom Begin Here: The Civil Rights Movement in Huntsville" in the museum's main building.

Hamlin's thesis exhibit “This is Rocket City U.S.A., Let Freedom Begin Here” was on display for three months at Burritt on the Mountain.

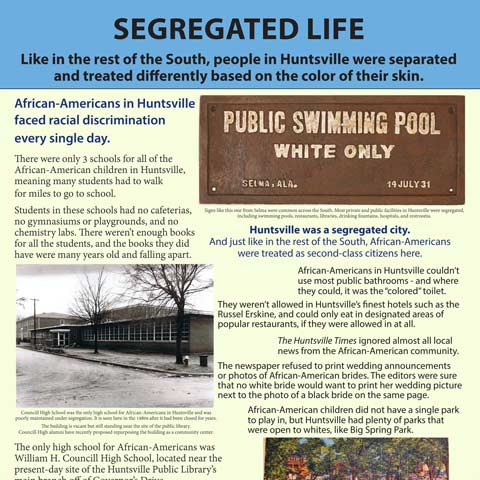

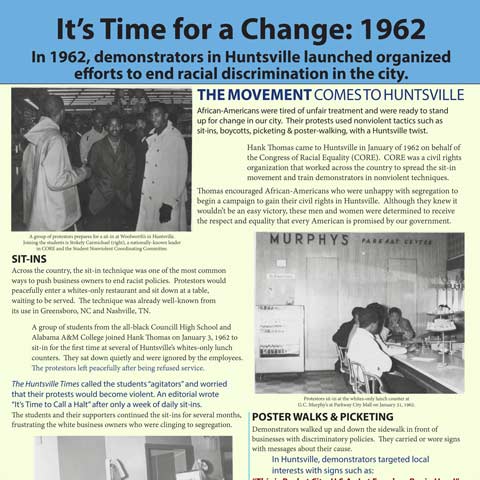

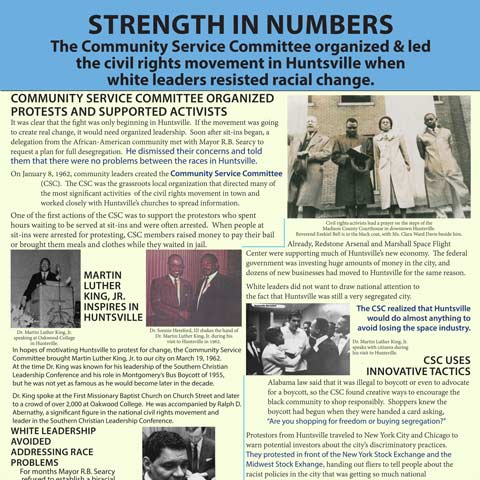

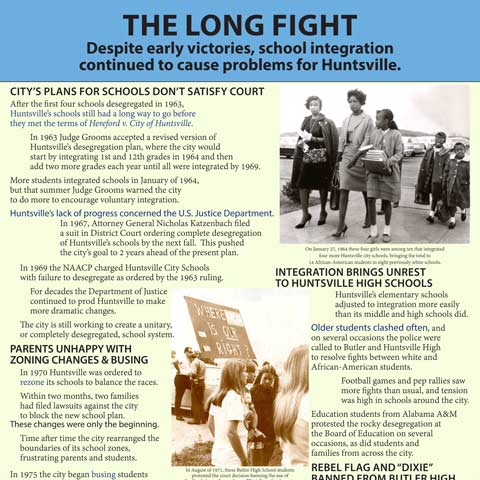

With its title taken from a quote seen on the sandwich boards of black protestors in the 1960s," This is Rocket City U.S.A., Let Freedom Begin Here" examined the city's complex civil rights history. "I didn't just want people to take away that we were the first to desegregate, but that it took a lot of work to be the first it wasn't just smooth sailing," she says. "This was still 1960s Alabama and there was a good bit of violence and pushback from the white community during that first year of activism. Protestors were still putting their lives on the line."

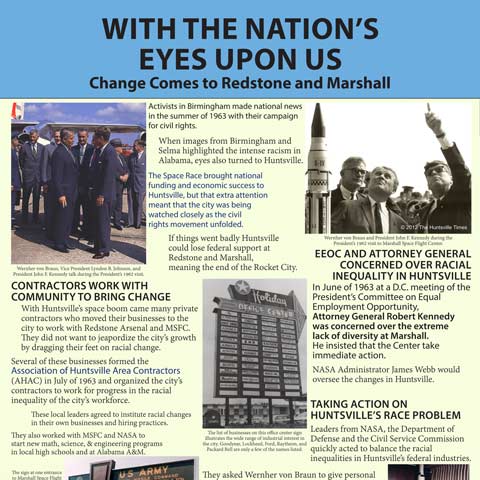

It helps that Huntsville's leaders were under intense pressure from the federal government at the time to avoid the kind of publicity that other cities in Alabama were garnering for their stance against integration. "There were clear messages from NASA administrators saying we can't have these headlines or we're not sending federal dollars to your city," she says. "So organizers in the black community put themselves out there and were savvy about hitting the city's weak spot, the federal dollar, to lead a successful grassroots effort."

And it's those protestors, among them Dr. Sonnie Hereford III and his son Sonnie Hereford IV, who really deserve the credit for Huntsville's desegregation according to Hamlin. "Dr. Hereford was one of the only black doctors in Huntsville, and his son was the first black child to enroll in a public school in Alabama," she says, referring to the no-longer-extant Fifth Avenue School. "Yet that's not taught in school - you hear about Selma and Montgomery but not Huntsville. So that's why I wanted to do an exhibit on it."

The seven-panel installation stayed on display at Burritt for three months, giving Hamlin numerous opportunities to present it to the general public and visiting groups of public and home-schooled students. After it closed, she stayed on as park manager for another year before leaving to complete the writing component of her thesis. "I wanted to look at the historical context of the exhibit, the process of creating it and what I wanted the audience to take away from it," she says.

And now that she has done so - successfully defending her thesis last month and ensuring she will graduate in a few weeks' time - she can dedicate herself more fully to growing Wolf Gap and restoring a historic home on her family's property that she hopes to one day turn into a museum. "Ultimately I wish every student in every class could go to a museum site," says Hamlin. "But even if they can't, they can still see what it's like to actually churn butter or use the tools that people were using in the past."

That's particularly important in a world that's changing as fast as ours. "My grandparents' world is lost to children growing up today," she says. "So this will help them see how we got to where we are now - and if you think history doesn't apply to every day life, then you haven't been paying attention!"

Gallery

Contact

UAH Department of History

256.824.6310

history@uah.edu

publichistory@uah.edu

UAH School of Graduate Studies

256.824.6002

gradschool@uah.edu

Wolf Gap Education Outreach

256.527.0536

WolfGapTN@gmail.com