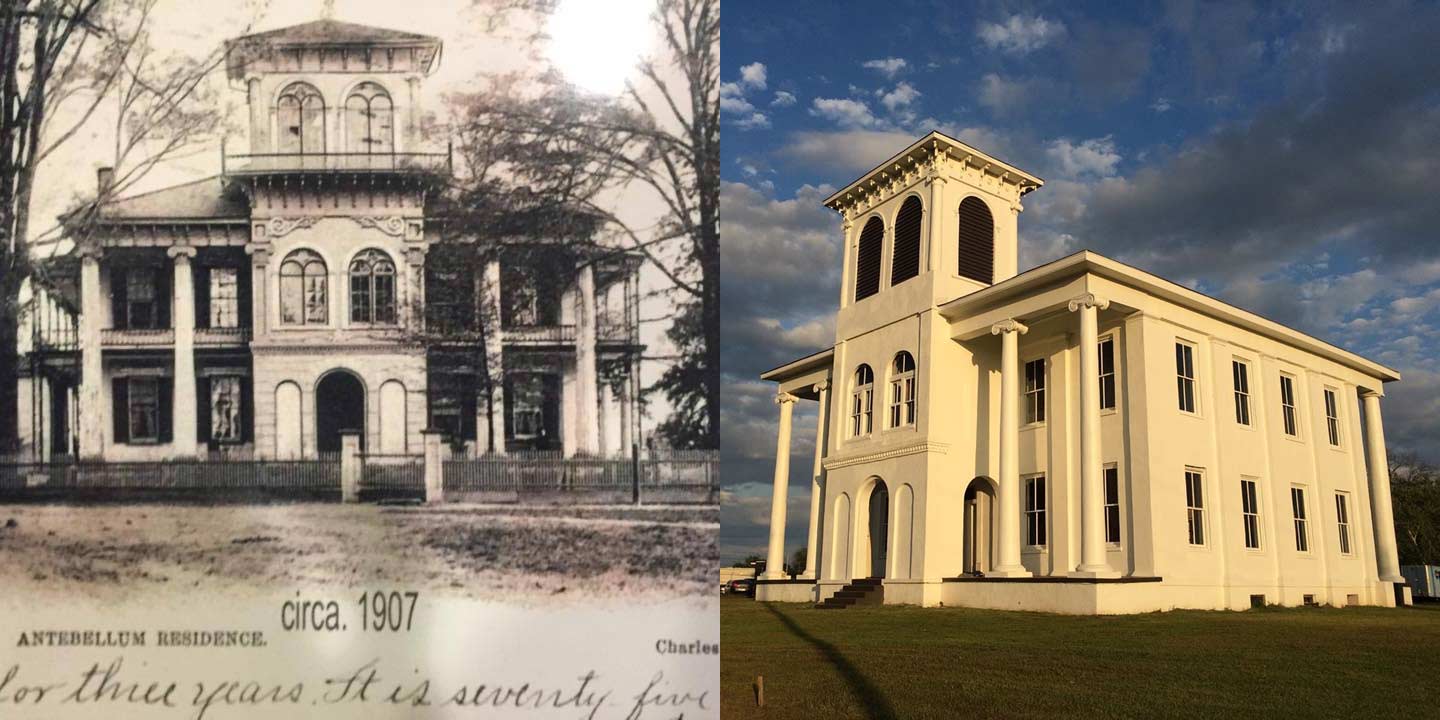

The 19th century Drish House in Tuscaloosa, Ala., was recently re-opened after being renovated by UAH alumna Nika McCool. It is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Jemison School–Drish House.

Nika McCool

The Tuscaloosa County Preservation Society (TCPS) knew it would take a special person to tackle the immense job of restoring the historic Drish House to its former 19th century glory. It would have to be someone with both the vision to see past the building's crumbling exterior and bat-infested interior and the fortitude to stand up to the ghost of Mrs. Drish, said to have haunted the property since her husband's death. Fortunately, they found the perfect candidate in Nika McCool, an alumna of The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH).

"I didn't have any idea where the project was going to take me - I had no clue - but I thought that we would puzzle out a way forward as we went along," says McCool, who holds bachelor's degrees in English and history and a master's degree in history from UAH's College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences. "Most projects I approach with a positive attitude: why would I not be able to do this? I think that's all the History Department. I was blessed to be mentored by a wonderful faculty who taught their students to think critically and be confident in our abilities. They never gave you a choice when faced with a difficult project - you just had to do it! So I've taken that attitude forward."

McCool previously renovated the Foster-Murfee-Caples House, located in Tuscaloosa’s Druid City Historic District.

Nika McCool

The Drish House wasn't McCool's first restoration project. A year before, a run-down three-story antebellum mansion located in Tuscaloosa's Druid City Historic District had caught her eye. "It was immediately attractive, this crumbling vintage house," she says of the Foster-Murfee-Caples House. Built in 1838 by slaves and given as a wedding gift from Marmaduke Williams to his daughter Agnes, the Greek revival structure eventually fell into disrepair after being subdivided into apartments in the early 1900s.

"I hadn't done any home renovations before, but I couldn't think of a reason I couldn't do it, so I bought it," she says. And when she learned from an architect friend that she could receive a tax credit for up to 20% of the cost of restoration if she adhered to historic preservation guidelines, it only added to her determination. "It took six months," she says, crediting "a great general contractor, four sons, and an engineer for a husband" for helping her to accomplish the task so quickly.

And at the end, she had more than just a fabulous-looking historic home to show for it. The TCPS honored McCool with a "Brick & Mortar" project award for her work - and an offer. "They said, we'd love to present you with this award, and by the way, we have this other house we'd like you to look at," she laughs. That "other house" was, of course, the Drish House, which the TCPS had purchased in 2013. "They bought it to keep it from being demolished and they'd done the minimum to stabilize it, but they didn't have the funding to do much else."

Needless to say, McCool accepted the offer. "It needed to be saved and I thought we could do something with it, though I wasn't sure what at that juncture!" she says. She started with an overhaul of the exterior. "There were things that had to be done to prevent the house from decaying further and to make it safer." At the same time, she partnered with Gene Ford, an architectural historian with the Office of Archaeological Research at the University of Alabama, to nominate the Drish House for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places.

"We had to justify the inclusion of our structure on the register - why it's historically and architecturally important locally and at the state level," she explains. The issue they faced, however, was deciding which era in the home's 180-year history was the most significant. "It had really been too many things. It was a private residence, a public school, a famous auto shop, and a Baptist church before the TCPS bought it. It had even appeared in an iconic image of the Great Depression taken by Walker Evans."

Twice over six months their application was returned, requiring them to delve further into the home's history. "After we got it back the second time, we were like, I don't know how much more research we can do!" she says. "We looked at so many primary sources that I don't know how much more we could have come up with." Ultimately, however, their hard work paid off - "I really owe Gene," she laughs - and the structure was added to the list as the Jemison School-Drish House in 2015.

The house was originally built by slaves as a private residence for Dr. John R. Drish but was later used as a school and a church, among other things.

Nika McCool

With that acceptance thus ensuring McCool's eligibility for the historic tax credit, she was then able to focus on renovating the building's interior. She decided to retain the floor plan used by the church rather than turn it back into a home, with the intent of using the Drish House as an event venue. "It's in the middle of a traffic circle, so I imagined it being a center of creativity and learning," she says. "The things that we have in Tuscaloosa that are from the capital era and survived the Civil War are pretty important to all of us."

She also set a firm deadline for the completion of the home's renovation by agreeing to host a wedding in mid-May. "It was hard, hard, hard, but we got our certificate of occupancy the Thursday before the event," she says. That's not to say the renovation is in any way complete. "I don't know if we'll ever get back to the Drish House's heyday in 1906 - there's just so much detail missing" says McCool. Yet she is hopeful that the newly formed "Friends of the John R. Drish House" can help address the next phases of the restoration. "The community, including the Drish Family, is so interested in the house, they should be part of the process."

For now, though, McCool is just grateful to have played a part in preserving both the house and the legacy of the slaves who originally built it. "The feeling in the preservation community is that we all benefit from having it saved," she says. "We haven't found any Drish slave narratives, but this is the work of their hands. I feel really privileged to say, 'we may not remember your name, but here is something you built, your legacy is in these bricks and to help that go forward a little further."

Gallery