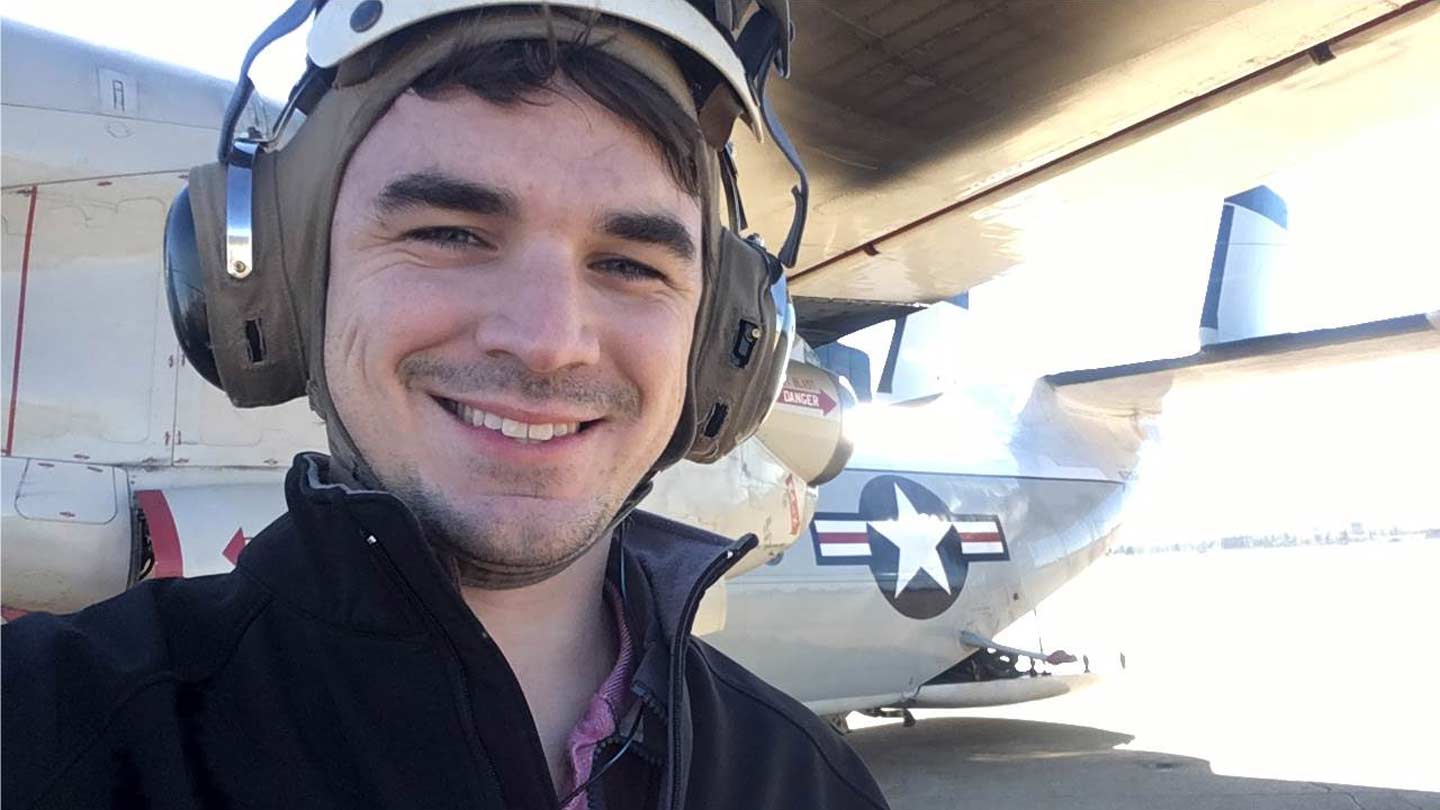

Markus Murdy while observing at-sea flight operations.

Before he was a student or an alumnus at The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH), Markus Murdy’s family would take vacations from Janesville, Wis., to the Gulf of Mexico’s beaches and stop by the 360-foot tall Saturn V rocket vertical model in Huntsville on the way back north.

"Quite surreal to later go to school across from that rocket, and then work for a summer on a cutting-edge new composite cryotank at NASA where that rocket was designed and in some of the buildings where they figured out how to make that rocket’s tanks, to be close enough to Cape Canaveral to visit and watch present-day rocket launches, and to design and fly rockets of my own," says Murdy, who graduated in 2015 with a Bachelor of Science in aerospace engineering. "I was very blessed during my time at UAH."

Since graduation, Murdy has built a career in the fields of his fascination with the U.S. Navy Naval Air Vehicle Systems Command (NAVAIR) at Fleet Readiness Center-Southeast in Jacksonville, Fla.

"Aviation has been in my blood for a long time. When I was 10, my dad and I built four Blue Angel F/A-18 models and hung them in the diamond formation from my bedroom ceiling," he says. "To work on the real-life, supersonic version of the models I've had in my bedroom is awesome. By now, most friends know that visiting an aviation museum or watching an air show with me is bound to include details beyond the provided narrative."

The vehicles NAVAIR services are steps away from the office, Murdy says.

"When we have problems, we can walk over and observe the problem in real time, crawl around inside the vehicles to observe the component's interaction with other parts, and gain insight on how any repair might affect other systems. My work friends know that any day I'm on a jet is a good day, from my perspective. I love working at an airport."

Immediately after graduation Murdy worked for RadioBro Corp., a UAH graduate-owned small business in Huntsville.

"I tremendously enjoyed the opportunities working for a small business presents. With a small team, you have more impact to change the design and then have ownership when the design goes to production," he says. "Smaller teams can move in a nimble fashion to quickly solve the client's problem while working around potentially complicated idiosyncrasies."

While at RadioBro, Murdy helped support the firm’s Cyclone data acquisition system on an FAA certification project.

"I loved flying to test sites around the Southeast, integrating Cyclone onto the airplane – real hands on work, taking apart the airplane to get our sensors in the right spot, building the mounting fixtures for those sensors, sitting in the cockpit or on ladders setting up the machine/pilot interface and performing ground tests, and then operating the system in real time with engines turning!"

He says it was humbling to realize he was the system's expert and when people asked questions, he’d better know the answer or be honest enough to pause and go find the answer, because it has to be the correct answer.

"Additionally, in my interactions with the test pilots and data analysis folks, I was exposed to the real life implementation of many topics I learned in a UAH classroom. These included topics like stability and control, aerodynamic theory and measurements and instrumentation installation/calibration. It's one thing to solve a test problem in an air-conditioned classroom. It's quite different working through a weight and balance issue in a hot, humid, buggy hangar with the test and data folks. Seeing how they understand these concepts was very insightful. It was incredibly rewarding to take the lessons learned and participate in the design of the new updated Cyclone."

The move to NAVAIR meant a change to working for the government.

"I enjoy seeing the differences in the two organizations and finding positives in how each operates," he says. "As an engineer, at the end of the day you want your product to be relevant. When we are finished with our vehicles, they leave to support national security missions all over the world. I find that to be rather relevant in today's global scene."

In Jacksonville, his experience has been on the rework and sustainment side of the project life cycle.

"This type of engineering presents its own challenges, as the design has been set and the system has been operating, in some cases, for more than 30 years this way," says Murdy. "We take in a variety of jets and components for rework. The fun part is finding how to get these parts back to as close to like new as possible within the constraints of the design and usage. I've had the privilege to watch at-sea flight operations and visit our facilities in the Southwest to learn how a large organization with multiple sites manages communications, policies and product quality control across multiple time zones and local environmental sensitivities."

Subjected to the effects of corrosion and the punishing takeoffs and landings, normal civilian airplanes in the sea environment where Navy vehicles operate would soon be unflyable.

One thing Murdy was known for at UAH was distributing business cards with his major and contact information.

"I made my first business cards for when I presented on work from my NASA internship. To me, part of being a successful professional is acting like you've been here before," he says. "I knew I'd be meeting many people the day of my presentation and wanted to make a professional impression. As a student I quickly learned that, while we as engineers must be able to do the math and science parts of our jobs, building a strong network within the aerospace community is also important."

Participating in the International Astronautical Congress, Von Braun Symposium and the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) regional student conferences and the national SciTech conference were highlights of Murdy’s time at UAH. He says he chose UAH over several Big Ten schools that were closer to Wisconsin, as well as other well-known engineering schools.

Two things that sealed the deal were the significant financial/tuition support offered by UAH, which meant he could finish engineering school with little or no debt, and that he saw students in the Engineering Design and Prototyping Facility (EDPF) actively making components for a project outside of class when he visited. Commonly called the machine shop by students, the EDPF is one of the largest facilities of its kind in the nation.

"That UAH would enable and support such activity –in this case, Space Hardware Club – meant that I could actually participate, experience the results and learn from the lessons that extracurricular engineering projects teach," Murdy says. "To me, UAH represented a place that was big enough to have industry connections, both national and local, like Redstone Arsenal/NASA and in Cummings Research Park, while being small enough to actually get my hands dirty. The student machine shop in Tech Hall was something unique that I hadn't seen in other campus tours. I know other campuses have student machine shops, but to see that UAH made its shop's visibility a priority stood out to me."

Murdy says he found tremendous value at UAH in the accessibility of participation in hardware focused groups like Space Hardware Club, with faculty support from Dr. Francis Wessling, and the opportunities to bring his designs to actual hardware with the capabilities of the EDPF and the mentoring of Steve Collins, machine shop supervisor.

"I hope UAH continues to support and grow the machine shop as an outreach to show engineering students how their designs are made," Murdy says. "

When the designer makes the part, he understands production limits and improvement opportunities better than if he simply exchanges drawings with someone else who actually makes it for him. As an engineer, I typically don't operate the machines that do the work I order. Having that machining and shop experience from UAH has enabled me to speak the same language and to work more closely with the machinists and artisans doing the work."

He says the Space Hardware Club, with support from Alabama Space Grant Consortium, UAH Research and others, provided a training ground to learn how to start projects from a blank sheet of paper, work with a team of engineers in different disciplines, manage timelines and budgets, interact with project stakeholders, resolve conflict and deliver a product that completes the mission.

"Knowing your hardware will be on the flight line motivates diligent study of all aspects of the flight to ensure your hardware comes back safe," Murdy says. "Many fun opportunities were directly enabled through their support. Friendships forged during late nights in the lab, at the test stand, or writing reports have been crucial in finding each of the jobs I've been blessed with."

The engineering he does now is of a different perspective than what UAH mechanical and aerospace engineering undergraduates learn, he says.

"When I was at school, much of the focus was on design. I now work with operational systems, that have already been designed, and now need engineering support for maintenance, rework, and overhaul," Murdy says. "I love working on things that fly, whether in space or the atmosphere, and look forward to doing that for quite a while.

"Much of our school training dealt with the structural side of vehicle engineering. I purposely chose to work, then, on mechanical subsystems at each of my jobs thus far to broaden my experience within aviation. I look forward to getting involved with another design project in the future and hope to leverage my subsystems experience with my structures schooling to enable efficient vehicle integration."

The journey to living his dream has been helped by tremendous friends at church, in the community, at work and at school who supported him, Murdy says.

"I would not be where I’m at today without their support and encouragement. I miss Huntsville and look forward to visiting soon," he says. "To the people who have served our country in the armed forces, thank you for your sacrifice and service. We can't understand the difficulty of what you go through, but we can still be grateful and respectful."

Learn More

Contact

Mallie Hale

256.824.6549

mallie.hale@uah.edu