UAH nursing professor – and mother – uses education to push for answers

Dr. Beth Barnby is assisted by student researchers Ranya Zahran, Megan Hillgartner, and Jennifer Navarro.

Dr. Elizabeth Barnby didn't attend The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH) so she could get a job; she already had one as an emergency room nurse. She attended so that she could learn more about Tyrosinemia type 1 (TT1), a rare and often fatal metabolic disorder that affects 1 in every 50,000 babies born in the U.S.

Dr. Barnby, it turns out, has two children with TT1. She's also now an assistant professor and the undergraduate program director of UAH's College of Nursing. But when she and her husband moved to Huntsville in 2009, all she wanted to do was help her son and daughter.

Dr. Beth Barnby's research focuses on Tyrosinemia type 1, a rare and often fatal metabolic disorder.

"At first I attended UAH so I could understand the research studies," she says. "But during the time that I was getting my nurse practitioner degree, both of my children became more stable and there were less questions about what I could do for them."

So she decided to turn her attention toward helping others instead, an effort she thought would be strengthened by first earning her Doctor of Nursing Practice degree from UAH. "I thought if I had a doctorate that people would listen to me," says Dr. Barnby of her motivation.

Initially she planned to focus on improving newborn screening for TT1, which is often misdiagnosed as sudden infant death syndrome, or SIDS. But once she learned of a new standard being set by the Mayo Clinic that would ensure improved new born screening for TT1, she says she switched her concentration to providing care for those diagnosed with TT1.

"My scholarly project was on a continuing education program for nurse practitioners, teaching them about how to take care of kids with TT1," she says, adding that her research will soon be published in Pediatric Nursing. "I also started teaching the pediatric portion of the College's undergraduate program."

But Dr. Barnby knew there was still more she could do. "I realized if I became more educated about the science of TT1, it would help me design research studies," she says. "So I started taking biology classes here, and the only one that didn't conflict with my schedule was Dr. MacGregor's."

An assistant professor of physiology in UAH's Department of Biological Sciences, Dr. Gordon MacGregor's research specialty is the body's regulation of water and electrolyte balance. He's also, says Dr. Barnby, "a very smart researcher who is passionate about understanding the underlying pathophysiologic mechanism of complex diseases"

Before long, she was able to inveigle an invitation to work in Dr. MacGregor's mouse lab, where she says, "he eventually realized I knew what I was talking about had a legitimate scientific hypothesis about TT1."

My goal is to have a better treatment to keep TT1 kids alive long enough until we have gene therapy.

That hypothesis? That if a mouse with another inborn error of metabolism, called alcaptonuria, could be bred with a mouse with TT1, the offspring who inherited both would be prevented from dying because the alcaptonuria would block the TT1.

But when they looked at the cost of inducing alcaptonuria in otherwise healthy mice, says Dr. Barnby, "it was out of our price range!" So instead she and Dr. MacGregor opted to focus on improving the treatment of TT1, which is currently limited to the use of 2-[2-nitro-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]cyclohexane-1,3-dione (NTBC).

"NTBC is the only pharmaceutical to use for these kids, but it's a drug that might introduce neurocognitive changes," says Dr. Barnby. "So my goal is to have a better treatment to keep TT1 kids alive long enough until we have gene therapy."

And that starts with a lower dosage. "Humans are on a very set dose" she says. "But we're experimenting on the dosage in mice to find out if a lower dose will work and avoid cognitive decline."

The first step, of course, is getting the right mice. Dr. Barnby says a breeding pair costs $2,500, and that when they breed, only one-fourth have TT1; another fourth are normal, and the remainder are carriers. Thus, the second step is getting enough of the right mice.

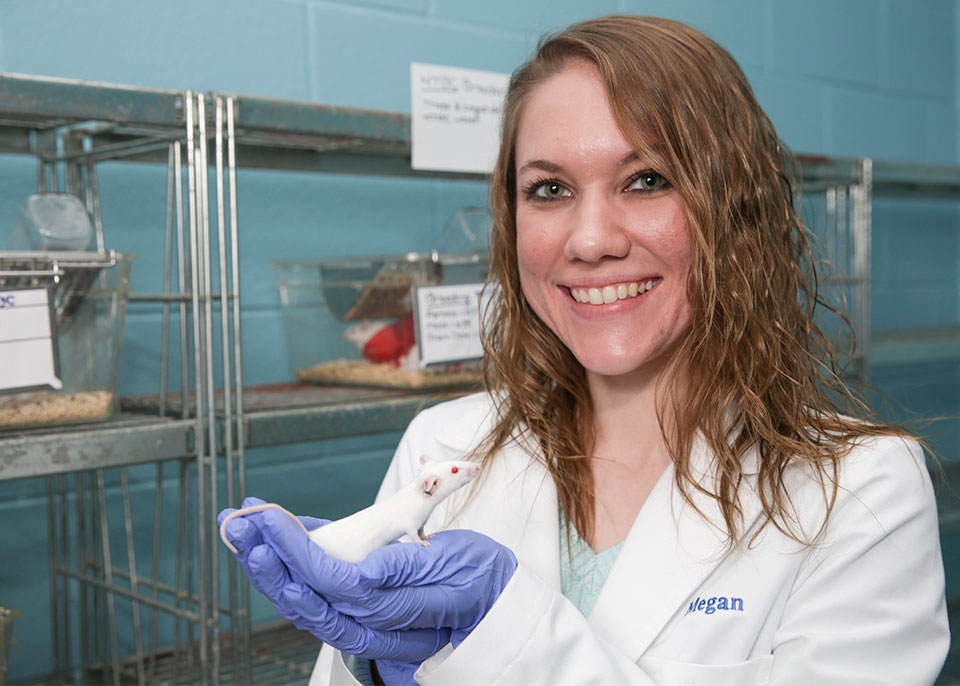

Student researcher Megan Hillgartner works with mice to help understand the neurocognitive affects of NTBC.

That's the job of student researchers Megan Hillgartner, Jennifer Navarro, and Ranya Zahran. "I know when we test the mice that we need a certain number of test subjects," says Hillgartner, who eventually hopes to earn a Ph.D. in either biology or biotechnology. "So breeding and enhancing our colony determines our timeline."

Eventually, she continues, they will have enough mice with TT1 to begin testing them using specially made mazes to assess any neurocognitive decline as a result of NTBC treatment. But it's not a fast process by any means, and that can be a source of frustration for Dr. Barnby.

"We have to keep trying a few new things without doing it all at once, because we don't want all of our eggs in one basket," she says. "But I want everything right now! I'm about the kids that are out there right now with the disease."

As for Dr. Barnby's own kids, "they're ok today," she says. "They come here every summer and teach the nurses what it's like to be a transplant survivor, and my daughter also talks to nurses at the hospitals through the Alabama Organ Center."

But one day, she hopes, through her research, future generations won't have to endure what they did. "If we learn about this," she says, "there's a potential to cure it."

Learn More

Contact

Dr. Beth Barnby

256.824.4231

barnbye@uah.edu