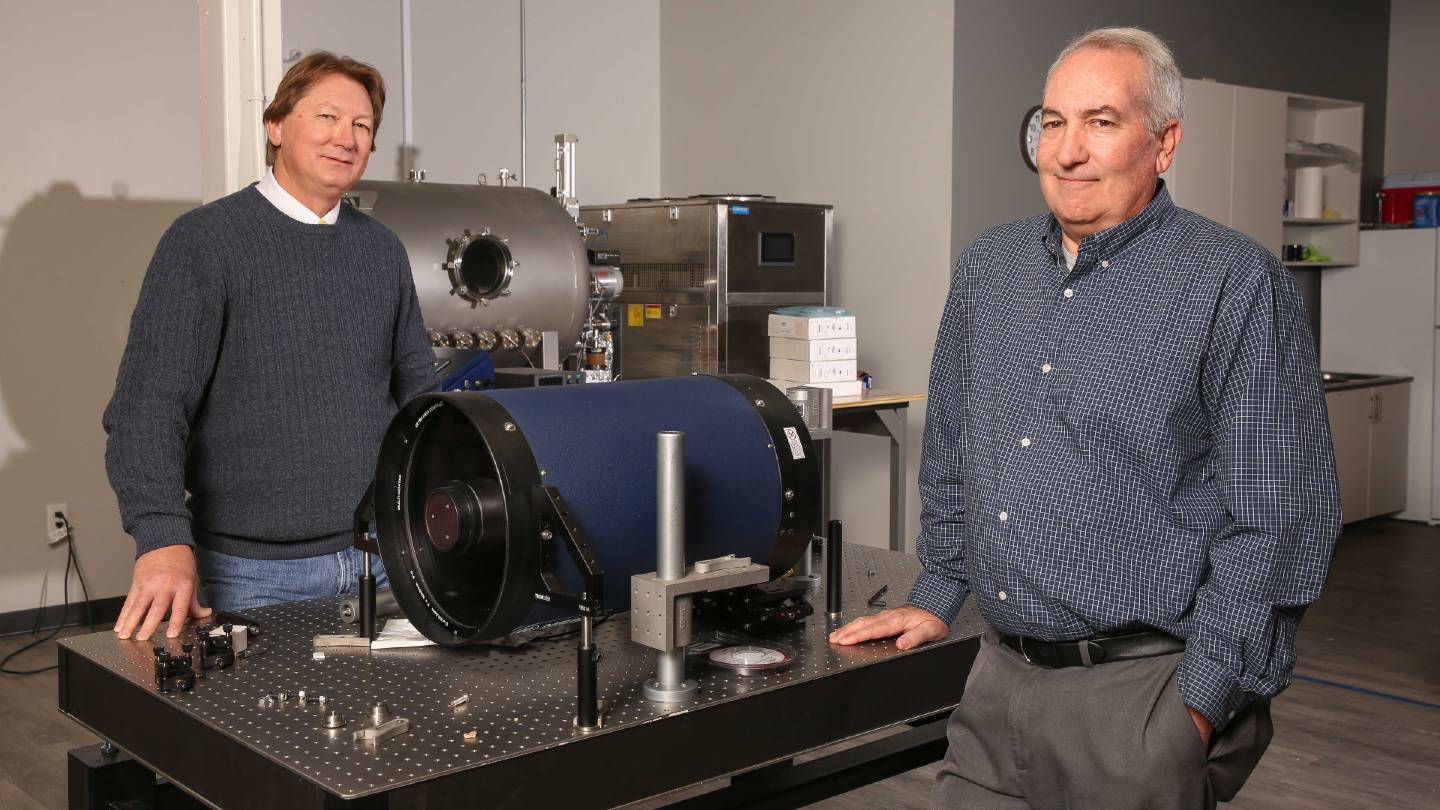

Dr. Gary Maddux, left, and James Clark have grown the SMAP Center exponentially since 1987.

Michael Mercier / UAH

What began with two new University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH) Research Institute employees trying to serve a couple of specific needs for the Army has evolved over 36 years into the Systems Management and Production (SMAP) Center, the largest organizational center and the largest student employer at the university.

Directed by Dr. Gary Maddux, SMAP is an example of what adhering to a win-win paradigm can produce over time.

“What we do with potential clients is, we sit down with them and say, ‘What do you need done, and how can we help you to do that?’” says Dr. Maddux. “We don’t tell them what to do; we ask them what they need.”

When SMAP meets those needs at UAH, a part of the University of Alabama System, then everybody wins.

Today, SMAP has 300 employees, 100 of whom are students, and offers Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Math (STEAM) students from UAH and other universities opportunities to work part-time for SMAP clients like the U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command, the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Aviation & Missile Center, or other entities located on Huntsville’s Redstone Arsenal.

“Almost any tenant out there on Redstone, we have worked for,” says Dr. Maddux.

By employing SMAP students, the Army gains a pre-screened, teachable, part-time workforce with full time potential after graduation. The students gain a foothold in the employment door that includes mentorship, real-world experience, connections and a potential career path after graduation.

The combination has proven so successful that, since its formal 2002 creation as a center by the University of Alabama System Board of Trustees, SMAP has brought $100 million in indirect returns to UAH.

“Indirect returns means that you’ve covered the direct cost of labor, travel and materials, and indirect is what comes back to the university,” Dr. Maddux says. “Nobody else has come close to matching that.”

SMAP’s student employees are not limited to UAH. Students from universities as far away as Texas and Colorado are working with the Army through SMAP.

It all started back in 1987, when Dr. Maddux and the man he calls his “principal associate director,” James Clark, started as entry-level UAH computer programming employees.

“When we were hired, we were the first two non-engineering, non-science employees on the UAH Research Institute’s payroll,” says Dr. Maddux, a first-generation college graduate who grew up in Jackson County.

The university even had to create a new employment category for the pair.

“We were just a couple of overachiever guys, and nobody gave us much of a chance of doing very much,” he says. “Now, 36 years later, we are the largest research center.”

Clark’s first Army contract task was in networking.

“He was asked by an Army employee to network two computers to a single printer,” Dr. Maddux says. “That grew over the years into an Aviation & Missile Center relationship that now includes over 11,000 users there that we provide services to.”

For Dr. Maddux, the first Army contract involved developing a reliable paperless supply system.

“From there, we just kept adding students and employees and tasks,” he says.

“So, we grew to be as big as we are one task and one employee at a time. It took us 36 years to get here. You don’t just anoint yourself as being excellent in something, you have to grow into it.”

The pair quickly spotted the advantages for all concerned of employing university students who were studying in the STEAM fields as part-time SMAP workers, and that eventually evolved into the Students Working for the Army in Parallel (SWAP) program, through which student workers are contracted to the Army.

“We hire just about any version of students in fields including engineering, finance, logistics, accounting, management, information technology, even psychology and political science,” says Dr. Maddux.

One result of getting a couple of business students to run a center is that it then runs like a business, Dr. Maddux says. “Ninety percent of what I do is accounting. I count everything.”

That’s how he knows that since 2004, the SWAP program has had 290 students hired as civil servants by the Army. Defense contractors hired another 391, and 47 are employed by other government agencies.

“Seventy-four percent of students we hired ended up in defense, for a contractor or as a civil servant,” Dr. Maddux says. “So, every time I hire four students, three of them have a career out of it.”

Students benefit by working with SMAP in a variety of ways.

“If you’re working with us, you’re working in your field, and it’s going to make you a better student because you are applying your classroom learning to a real-world situation, and that keeps you more interested. Your experience informs your education,” Dr. Maddux says.

“The second thing is, a student working with us is going to have a security clearance,” he says. “On your resume, you are going to be able to list real-world experience. You’re also going to know people, people you have met as a result of your work experience.”

Part-time SMAP student employees also have the benefit of being eligible to be promoted by the center to full time once they graduate. Once they become full time, they are eligible for UAH’s tuition assistance as they pursue master’s and even doctorate degrees.

SMAP’s full-time employees work for clients on a variety of projects including 3-D printing, Cubesat technologies and an increasingly recognized capability in visualization.

Once a student is hired away, Dr. Maddux follows them in their careers. Over time, that practice has built up a large contingent of former SMAP employees who are now in decision-making roles.

“We have an infrastructure of former SMAP students and so we are recognized as an entity that is a great civil service recruiting arm for the Army,” he says.

A portion of the center’s indirect returns go into a discretionary fund, and some of that is used for outreach projects across north Alabama and the state.

For example, during the COVID pandemic every county in north Alabama benefited when, under a program through the UAH Foundation, SMAP’s internal “bullpen” of student employees who are not yet working for clients 3-D printed personal protective gear for healthcare facilities.

The center has worked with Jackson County Schools on enhancing security systems to keep students safer. And SMAP student employees have been involved in STEAM outreach to primary and secondary schools, assisting in the development of the next generation of students.

“It’s grooming our students to work on real projects with real outcomes and to make a difference,” Dr. Maddux says.

A recent STEAM project aligned SMAP with Bullock County in Alabama’s Black Belt. SMAP student employees helped convert an old school bus into a portable greenhouse, complete with solar panel power. The home of Bonnie Plants Inc. and a site location for solar farms, Bullock County’s students are learning about STEAM in ways that directly impact their locale, Dr. Maddux says.

“This keeps the kids interested, and they can learn about agriculture, solar and green energy, all from this one bus that can travel to the schools in Bullock County,” he says. “I want to address what is relevant to their own county. I want them to develop into the best they can be, whatever they want to be.”

The goal is to expand STEAM outreach into other Black Belt counties and eventually develop a network of shared projects between them.

Looking back over 36 years of evolution of the SMAP Center, Dr. Maddux says its future relies on the win-win framework of values that he and James Clark laid down as they took on their first contracts in the late ’80s and early ’90s.

“The best talent James and I have is recognizing talent in others and promoting it,” he says. “If you hire based on the intangibles, on talents, and then put people into a different system that is oriented toward their success, then things usually work out well. You have to treat your employees well and set them up for success.”