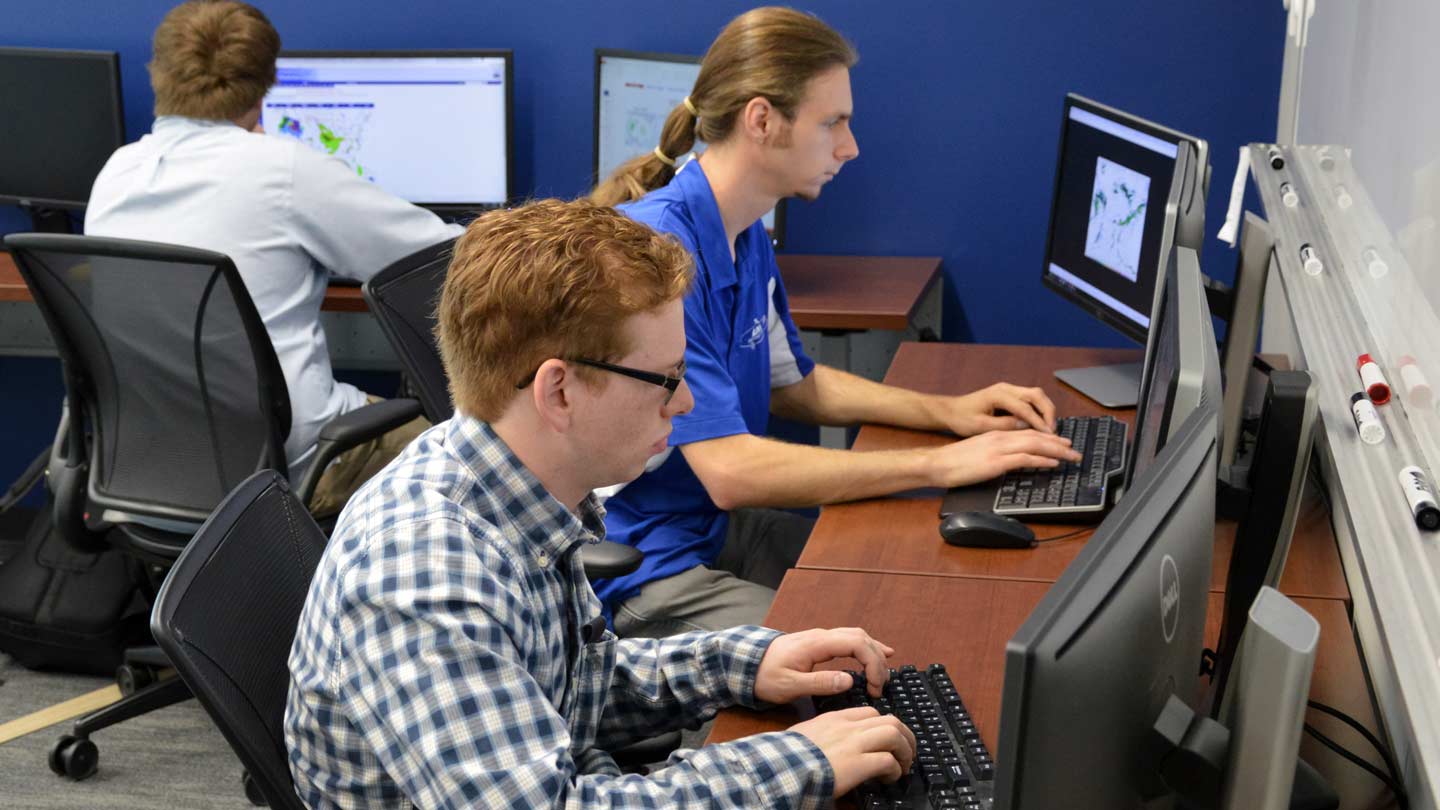

A team of UAH graduate students prepares a 7-day forecast they will present later to the ER-2 GLM campaign science team.

A line of thunderstorms flashes and rumbles over southeastern Kansas into Oklahoma and Missouri, sending clouds towering as much as eight and a half miles into the pre-dawn Easter darkness.

More than three and a half miles above those tallest clouds, Greg Nelson guides his NASA ER-2 high altitude aircraft to and fro over the most active storm cells, looking for lightning.

In UAH's SWIRLL building, a team of UAH students watch radar and satellite data, as well as forecast models, feeding up-to-the-minute “nowcast” weather information to NASA and NOAA scientists talking (indirectly) to Nelson to help him position each sweep so it takes him over storm clouds with the greatest amount of active lightning.

The ER-2 — a converted U-2 spy plane — uses a sensor conceived, designed and built at UAH to look at lightning at the same time a new lightning instrument aboard GOES 16, a new weather satellite parked 22,236 miles above the equator, sees those same lightning flashes over the Great Plains.

The main goal: By looking at lightning flashes over the eastern two-thirds of the U.S. during the next month, to confirm the new satellite sensor — the Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM) — is seeing and reporting the lightning flashes it should see and report, and that it has them in the right places on its map covering much of the western hemisphere. That's why it is important to first forecast and then "nowcast" where the lightning will be.

"In mission mode, our job becomes to pick a spot, a lat long (latitude and longitude) the pilot can fly to," said Austin Clark, a master’s degree student at UAH and the team leader for the student forecasters. "In a lightning mission, the pilot's as good a nowcaster as we are. He can see the storms, but he'll check back with us before making any flight changes.

"We have to file a flight plan before he takes off, but the flight plan is dynamic, and deviation is the norm."

The student team — three graduate students, including Clark, and two undergrads, along with eight unpaid volunteers — has been at work with the ER-2 flights since early March, at first making forecasts for clear skies over Mexico, California and the Gulf of Mexico. To date, they have been some of the team's most difficult forecasting jobs.

"The hardest thing for us has been forecasting clear skies," Clark said. "That's probably because no one usually cares about clear skies."

Clear sky was needed to validate another new GOES 16 instrument, the Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI), which is five times faster and has higher resolution than the instrument it replaces on GOES 14 and 15. ABI is the satellite's primary instrument, watching the movement of clouds and water vapor across land and sea.

Clear sky (ABI can see cirrus clouds too wispy and thin for human eyes to pick out) over visually uniform surfaces (the gulf, the Sonora desert in Mexico and the Mojave desert in California) gives the science team an opportunity to compare what ABI sees with what a similar instrument aboard the ER-2 sees over the same areas at the same times.

"They want the satellite and the airplane to see the same things," Clark said. "But having to pinpoint stuff like that has been extremely difficult. It turns out the hardest weather to forecast is no weather at all."

With the clear sky portion of the mission out of the way, the flights lasting until May 19 (when the ER-2 will fly from its temporary base at Robins Air Force Base in Georgia back to its home base at NASA's Armstrong Flight Center in California) will be hunting for lightning.

"We built for the ER-2 a series of instruments to validate the GLM," said Hugh Christian, a principal research scientist at UAH and the leader of UAH's lightning research team. In addition to being one of the primary designers and scientists for GLM, Christian also led the development of the Fly's Eye GLM Simulator (FEGS), the lightning watching instrument carried aloft aboard the ER-2.

"We want to get a variety of different types of measurements over different types of storms," Christian said. "But we also want to get flights over places where there is good ground instrumentation, so we can see how well the space-based measurements compare to the ground-based measurements that have been going on for several years."

These ground-based lightning measurements come from several lightning mapping arrays: a network of instruments that use signals generated by lightning flashes — for example, high frequency radio signals — to track lightning as it passes through that area.

There are two such permanent arrays in north Alabama, one organized by NASA and the other by UAH, listening to different parts of the lightning signal. That makes north Alabama a priority target for the ER-2 if a lightning-active storm passes over during the next month.

There are other LMAs, ranging from Houston, Texas, to Wallops Island, Virginia, and from the U.S. half of Lake Ontario (the actual LMA is in Toronto, but that's Canadian air space) to the Kennedy Space Flight Center in Florida. The Lake Ontario, western New York and western Pennsylvania region within the Toronto LMA's territory is the target for an ER-2 flight on Thursday, April 20.

"There are a number of these sites that we'll be going over on a preferential basis," Christian said. While the ER-2's principal mission is to validate and calibrate GLM, that won't stop scientists from using that same information to study storms and how they evolve.

"The more information we get on a storm, the better we'll be able to understand the storm and the physics involved," Christian said.

With the NSF-supported VORTEX Southeast severe weather research campaign camped in north Alabama for several more weeks, that makes storms in north Alabama an even higher priority for the ER-2.

When a likely storm moves into north Alabama during VORTEX SE (such is expected to happen Saturday, April 22), scientists with a dizzying array of instruments from across the U.S. swing into action: The two local ground-based lightning mapping arrays (plus a temporary lightning interferometer here just for VSE), up to half a dozen research-grade Doppler radars, trucks and trailers laden with lasers and other instruments designed to probe and profile a the storm's structure as it passes overhead, dozens of weather balloons launched into the heart of the storm, several portable weather stations, and NOAA's P-3 Orion airplane, which uses its two Doppler radars and other instruments to look into the storm from the side and above.

Add to that NASA's ER-2 and, perhaps, some GLM data to be named later (since the instrument isn't technically operational yet), and storms crossing north Alabama and the VORTEX-SE domain during the next month will keep few of their secrets.

"It's the icing on the cake," said Larry Carey, chairman of UAH's Atmospheric Science Department. "We will be able to do a lot of science from this."

Years before he ever thought about forecasting for instruments flying in airplanes on the edges of space (or at least above 90 percent of the atmosphere), Clark was a kid growing up in Ringgold, Georgia, just south of Chattanooga, watching the weather blow by.

"On April 27, 2011, I saw the strongest tornado in the Georgia record, an EF-4," he recalled. "I watched it come down from the sky. I couldn't see it touch the ground, but I heard that about five minutes later it hit the town.

"Of course, while I was watching all of this I was out on the front porch, which is the last place you're supposed to be in bad weather. But what good weather nerd isn't?"

Contact

Austin Clark

ac0028@uah.edu

Dr. Hugh Christian

256.961.7828

hugh.christian@nsstc.uah.edu

Dr. Larry Carey

256.961.7909

larry.carey@nsstc.uah.edu

Phillip Gentry

256.961.7618

gentry@nsstc.uah.edu