UAH RSESC researcher receives NASA Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal for advances in nuclear fuel

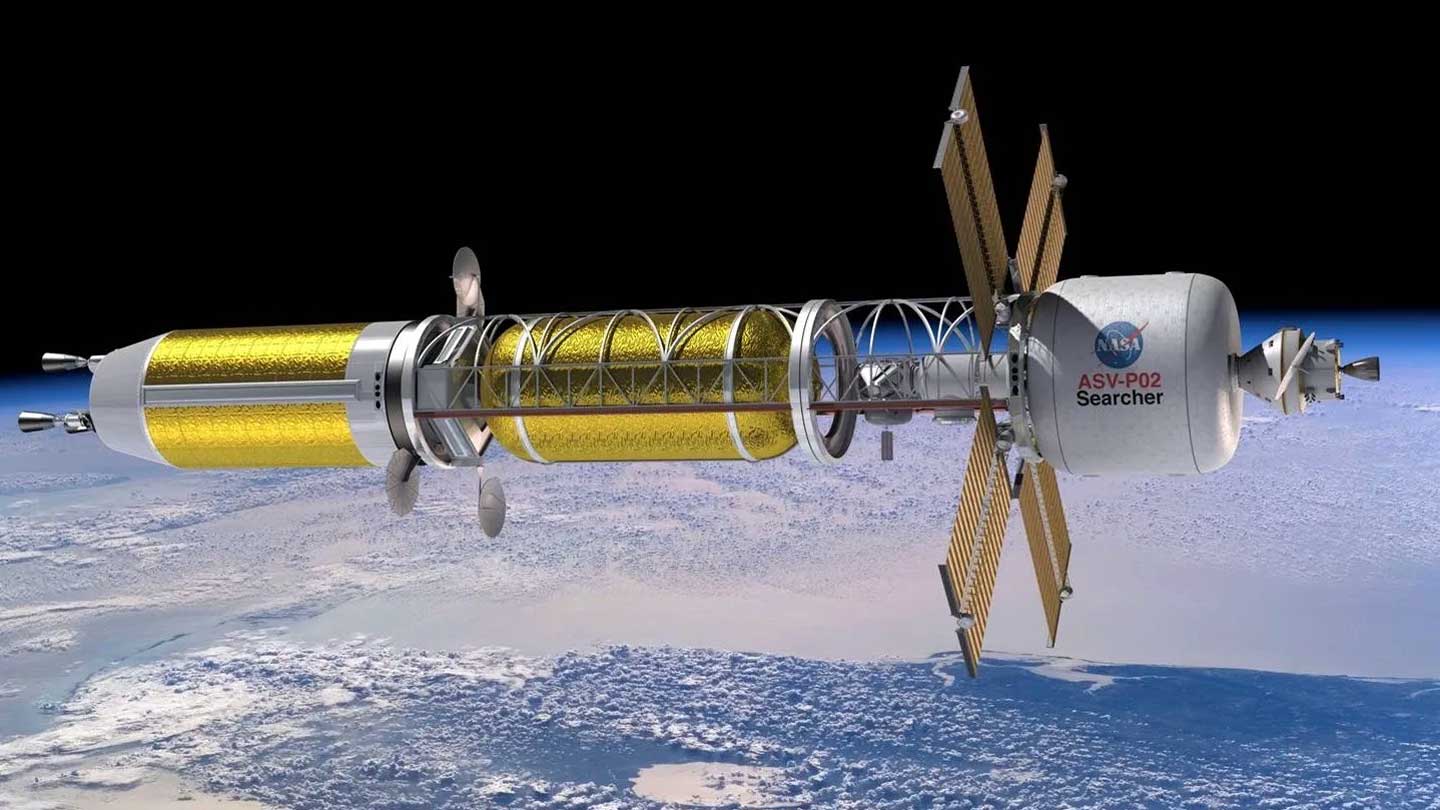

Illustration of a spacecraft enabled by nuclear thermal propulsion.

The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH), a part of The University of Alabama System, announced that Dr. Arne Croell, a researcher with the UAH Rotorcraft Systems Engineering and Simulation Center (RSESC), has been awarded NASA’s Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal (ESAM), one of the agency’s most prestigious honors for scientific accomplishment. Dr. Croell received the medal during a ceremony at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) on January 28.

Established in 1961, the ESAM is presented to both government and non-government individuals for “an unusually significant scientific contribution toward the achievement of NASA’s aeronautical or space exploration mission.” The award recognizes accomplishments that are fundamentally important to a scientific field or that enhance understanding within that field.

“Dr. Croell’s recognition by NASA underscores the world-class research conducted at UAH, the Rotorcraft Systems Engineering and Simulation Center and the strength of our longstanding partnership with Marshall Space Flight Center,” says Jerry Hendrix, director of the RSESC. “His work exemplifies his great team and innovative spirit, as well as the scientific excellence that defines UAH and our Center.”

(Center) Dr. Arne Croell of the UAH Rotorcraft Systems Engineering and Simulation Center receives ESAM award from NASA officials, Jan. 28.

The researcher joins a distinguished roster of scientists who have received the medal over the past six decades.

An internationally recognized expert in crystallography, Croell specializes in crystal growth processes critical to advanced technologies. His research focuses include detached Bridgman growth of semiconductor single crystals; nucleation and impurities in multicrystalline silicon for solar cells; radiation detection materials; thermo- and solutocapillary convection in crystal growth; vibrational convection in floating zone (FZ) and Bridgman growth; and the influence of external fields on crystal growth processes.

“I now work on materials for nuclear thermal propulsion (NTP),” the honoree explains. “The extreme environment of NTP is a fascinating challenge from a materials science perspective. As a crystallographer, I thought I could advance the analysis of these materials here at MSFC, employing X-ray diffractometry and other techniques to investigate uranium loss mechanisms. In NTP, the heat from a solid-state nuclear reactor is the fuel, and hydrogen is the propellant. The hydrogen is heated up to temperatures of 3000K in that reactor; it allows a specific impulse that is several times better than chemical rockets. A nuclear engine is not for launching; the thrust is not strong enough. It is only considered for space operations, such as traveling to Mars.”

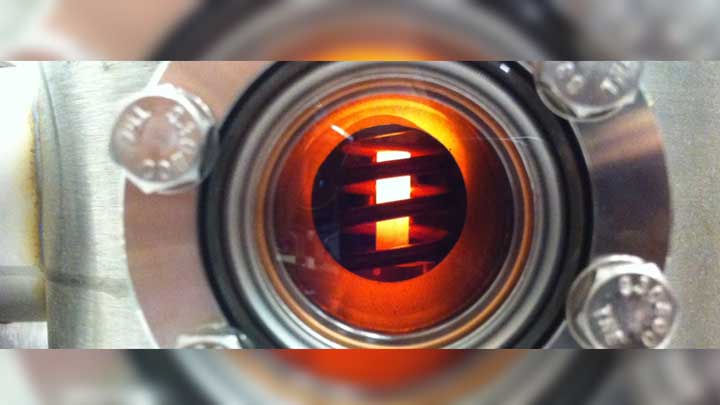

Nuclear Thermal Propulsion test.

Croell’s selection reflects decades of pioneering research in crystal growth and materials science, particularly in microgravity environments, where the researcher has served as principal investigator or co-investigator on five experiments conducted during crewed Spacelab and Spacehab missions; 11 experiments aboard unmanned Foton orbital satellites; 13 sounding rocket experiments; and three parabolic flight campaigns. At UAH, he was recently engaged in preparing experiments aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

“As you might imagine, NTP temperatures together with the hydrogen are attacking most materials including the uranium sources of the reactor,” the researcher notes. “I perform experiments where we heat small samples of possible reactor materials – for example, uranium-containing mixed carbides – in hydrogen at temperatures close to 3000K in steps up to six hours. We analyze the materials after each step with respect to mass loss, uranium loss, density, etc., trying to minimize mass and uranium losses through composition changes or small additives to the hydrogen flow.”

The process is detailed in a recent paper. Looking to the future of these kinds of advances, Croell notes his research is built on decades of foundational work.

“NTP is nothing new and was studied intensely until 1972 under Dr. von Braun, such as the Rover/NERVA program, etc., with a few starts and stops later. Those scientists and engineers made it pretty far, and in the end started using similar materials to those we are testing now. So, to use the old expression, we are standing on the shoulders of giants.

“Modern equipment, such as those used for sintering [a process that transforms compacted powder materials (metals, ceramics or plastics) into solid, dense and durable components], and the improved analysis methods today, allow us much better insights into corrosion mechanisms, and thus devise possible mitigation approaches,” Croell concludes. “So, from a materials science perspective, I am optimistic.”