Nandish Dayal, a senior nursing student, presented his research on sepsis to a local hospital.

UAH

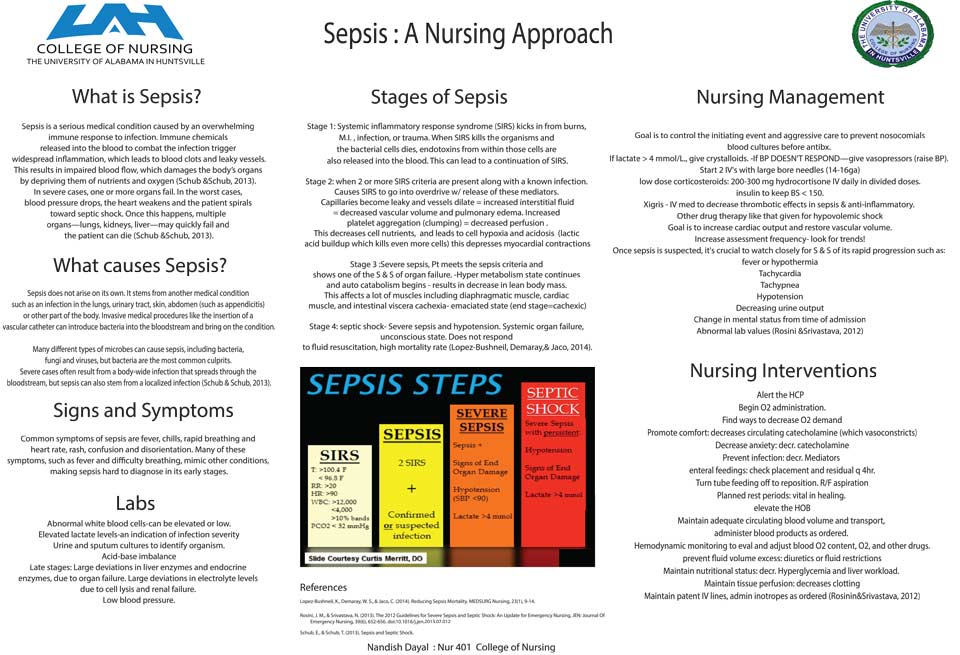

There are a lot of reasons why patients who are admitted to the hospital end up getting worse instead of better. Among them is sepsis, which occurs when the body's immune system response to an infection goes into overdrive, leading to widespread inflammation, organ failure, and even death.

"A lot of people think patients die of heart disease, but they'll die of a complication from the disease, and that complication is often sepsis," says Nandish Dayal, a senior nursing major at The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH). "Because it is not diagnosed, the patient is not treated for it and eventually succumbs to it."

Dayal initially began studying the illness last semester as part of his medical surgical nursing clinical. "My instructor, Sharon Spencer, asked us to supplement the clinical component with a research project," he says. "So we looked at the topics from the lecture schedule and we agreed that I would work on sepsis."

The assignment required him to research the prevalence of sepsis in hospitals nationwide, and then present his findings at a local hospital along with recommendations for its treatment. What he discovered was shocking: sepsis has become the leading cause of hospital deaths in the U.S., with its treatment costing hospitals billion of dollars annually.

I realized that the implications of my work extended much further, that they had practical applications.

"The problem is that it often goes unrecognized," says Dayal. "You learn what sepsis is over the course of two lectures in nursing school, but you may or may not encounter it during precepting. And if you don't, or you don't get enough practice with it, then you may not know what it is when you see it in the hospital setting."

As a result, he continues, doctors and nurses may end up making a misdiagnosis and prescribing the wrong treatment. "It's only when they go back to look at the charts, and see the patient's progress, that they realize the correct diagnosis is sepsis," he says. "By then valuable time has been lost, and that can mean fatal consequences."

It became clear to Dayal that any solution would hinge on early detection of the disease. Thus, he focused his end-of-semester presentation on two recommendations. "The first was to institute a code sepsis protocol from the moment a patient walks in," he says. "It would be similar to the code protocols that hospitals already have for heart attacks or strokes."

Like those more common code protocols, he explains, a code sepsis protocol would reduce the number of steps between diagnosis and treatment by giving doctors and nurses a clearly defined treatment regimen. "With it in place, an early diagnosis can be made and treatment can begin as soon as possible."

Dayal’s recommendations included a sepsis code protocol for early detection.

The second was to support the code sepsis protocol with a code team, a group of doctors, nurses, and technicians with special training to carry out the designated treatment regimen. "Unlike nurses, who have many patients, the code team is dedicated to and can focus their resources on the patient in need," he says. "So my suggestion was to have one for every floor."

As it turns out, the hospital staff to whom he was presenting not only agreed with his recommendations, but they went one step further. "The unit manager asked if he could use my research to supplement their current efforts to institute a code sepsis protocol," says Dayal. "I ended up presenting to many groups all over the hospital that day."

It was an unexpected outcome from what began as a classroom assignment, but one that he says helped him make the connection between research and the real world. "I did this as part of a clinical requirement, expecting to learn something myself. But then I realized that the implications of my work extended much further, that they had practical applications."

Of course while it may take years for his recommendations on code sepsis protocols to be implemented, Dayal himself won't have to wait much longer to make a positive impact on patients' lives. In just a few months, he'll graduate and become a full-time nurse. And when he does, he says with a laugh, "I'll definitely know what to look for - and what to do - when it comes to sepsis!"